TO MY READERS: HOW TO USE THE BLOG

Click Here

Borderstories.org has posted an article about the Border Patrol removal of the Candelaria footbridge. See it at:

http://www.borderstories.org/blog/?p=41

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 4512 views ) | permalink |

Check out the article from Texas Civil Rights Review about the Border Patrol removal of the Candelaria bridge. Gj

http://texascivilrightsreview.org/phpnu ... p;sid=1264

[ view entry ] ( 3717 views ) | permalink |

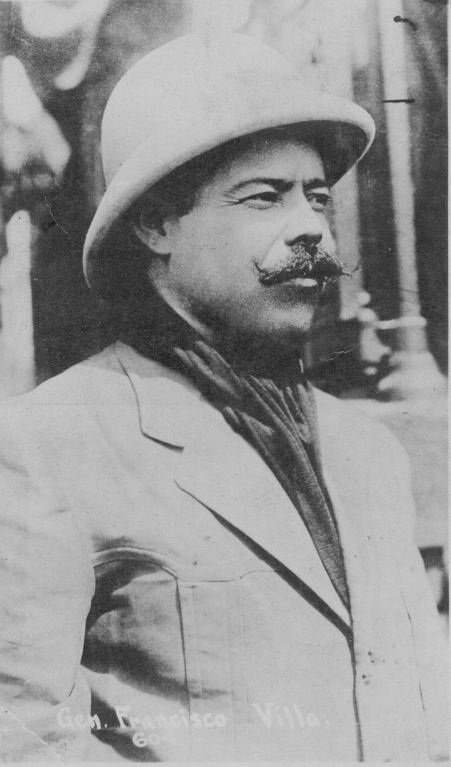

VILLA TURNS ATTENTION TO OJINAGA AND CAPTURES THE BORDER TOWN: A 1966 PEN FROM THE PAST BY ROSS MCSWAIN

Pancho Villa, well supplied after taking Juarez in mid-November 1913, sent three brigades of about 3,000 men to attack Ojinaga and entrap a long time foe, Gen. Luis Terrazas, who was trying to escape to the United States with gold bullion believed to be valued at $2 million.

The tree brigades, moving from separate areas of Chihuahua, traveled on horseback and on foot. Villa assigned 500 of his own brigade to the battle. The Gonzales Ortega Brigade, commanded by Torbino Ortega, had more than 550 soldiers. Fresh from the brief skirmish at Chihuahua City, the brigade also had two batteries of 75-millimeter cannon and some heavy machine guns.

A member of the Ortega brigade, Pedro Cabrajal, lives in Ojinaga. The 71-year-old veteran of Villa's army was a foot soldier. Until recently, he served as night watchman at the Ojinaga mayor's home.

Cabrajal and a childhood friend, Ignacio Rodriquez, 72, fought nearly a month at Ojinaga during that cold January in 1914. Although the two men grew up together in the Ojinaga area, they battled each other. Rodriguez was sergeant with the federal forces.

Recently, the two veterans recalled the battle during an all-day interview which started in the Ojinaga mayor's office and ended when a hard thunderstorm fell over the battleground as the two men pointed out positions from which each fought.

Cabrajal said the brigade he was in left Chihuahua City a few days before Christmas. According to records, it was on Dec. 22, 1913.

First contact between the Villa forces and the federal troops in Ojinaga came on New Year's Day, 1914.

Rodriquez said a cavalry patrol saw the first Villa troops moving on the city from the south. The patrol attacked the Villa soldiers and blew up an artillery piece. In the ensuing fight, the federal soldiers caused many causalities and caused the first contingent of Villa soldiers to retreat.

Cabrajal was not in the first fight with the federals, nor was Rodriguez involved. Rodriquez was in the federal troop encampment in the center of town.

On New Year's night, Cabrajal and other Villa infantry moved closer to the town.

"It was very cold," Cabrajal recalled, "Many had blankets and some of the soldiers had no shoes. Many hundreds of fires could be seen over the countryside as the men tried to warm themselves."

On the third day, federal troops, mostly on horseback charged the Villa lines. Rodriquez was one of them. Federal artillery supported the attack.

"We rode right into the first of them, hollering and shooting," Rodriquez said. "Many ran and were shot. Some were trampled under the horses."

Cabrajal said he lay in his shallow rifle pit and just fired his rifle at the first horseman he could see. Asked if he saw any federal troops fall, he could only shrug his shoulders. The fight ended in less than an hour. Villa artillery slammed into the federals and forced them to retreat to the town. Only minor casualties were inflicted on the cavalry troops, but Villa lost more than 100 men. An additional 130 were taken prisoner.

According to Mexican official records, Villa lost more than 300 men the first three days of the Ojinaga attack. About 200 were killed in the first skirmish. Another 100 died died in the federal attack on Jan. 3.

The prisoners were herded into Ojinaga and held overnight. They were shot the next day. Although Rodriquez knew of the Villa men being shot, he said he did not take part in the executions.

Cabrajal said the Villa forces retreated a second time from the battle to the base of a mountain just south of Ojinaga. During the withdrawal, federal forces ambushed a Villa column in a draw not far from the present site of the new Ojinaga railroad station.

"Hundreds were slaughtered there like cattle," Cabrajal said.

The draw, now called Arroyo del Muerte is filled in some. Many Ojinaga residents say more than 1,000 bodies were counted there after the battle was over. Most of the bodies were buried there, they say.

Rodriquez said federal troops were ordered to dig entrenchments about the town during a lull in the fight.

"We were heavily outnumbered, but we were ordered to make a stand," he said.

Rodriquez said many of the soldiers in the town sympathized with the Villa movement, including himself, but they had to fight or be shot. "Life wasn't worth much," he said.

The two men said they knew of many instances in which brother fought against brother and father fought against sons during the revolution.

Cabrajal, a teenager during the battle, joined Villa in 1911.

The old Villa soldier said he was recruited along with a number of relatives to fight by his brigade leader, Ortega.

"It was for a cause," he said. "My family was poor. We had no land. Ortega said when the fighting was over, everyone would be given land to farm."

Rodriquez, the federal trooper, joined the army because he couldn't find work. He said he liked the army because he was given clothes, food, a good place to sleep and he had a fine horse. He said he was given a peso a day (21 cents).

Commander of Rodriquez's troop was Capt. Marcus Cano. Cano, also an Ojinaga resident, died several years ago. The federal troops stationed at Ojinaga numbered about 350 regulars and about 60 reserves. Federal soldiers with Terrazas boosted the total to about 600.

Villa advised of discontent among brigade leaders, sent an additional 2,000 men into the Ojinaga battle on Jan. 6. he directed Martiniano Servin, an artillery commander to take command of the Villa forces until he could arrive on the scene.

On Jan. 10, it was announced that Villa was with his troops. A stream of refugees, ignoring sniper fire, fled Ojinaga to Presidio. Now more than 2,000 refugees were interred there.

On Jan. 11, Villa mounted the final attack on Ojinaga. He sent a column of 800 men to attack the town from the south, led by his generals Hernandez and Jose Rodriquez. Just west of the town, Villa placed his artillery in an area between the Conchos and Rio Bravo (Rio Grande). Villa with 900 men under his direct command, and Toribio Ortega's brigade reinforced to 700 men, started advancing from the north just at daybreak.

Salvador Mercado and Pascual Orozco, federal forces leaders, directed the defense of the city from the old customs house.

Pedro Cabrajal, the Villa foot soldier who still lives in Ojinaga, said the rifle fire was intense from the town as the Ortega men advanced across the chaparral area, immediately across from where the international bridge is now located.

We ran and hollered "Viva Villa", Cabrajal sid with a gleam in his eyes.

Ignacio Rodriquez, a federal soldier during the night now a retired railroad worker living in Ojinaga, said the Villa forces moved out of the draws and arroyos surrounding the town and started swarming toward them.

"Hundreds and hundreds came yelling and shooting," he said. "We were frightened but our officers would not let us leave the trenches. They told us to shoot."

Villa's artillery pounded the city and the trench fortifications. Some of the shells screamed over the Rio Grande and exploded within several hundred yards of Presidio.

Carlos Spencer, a storekeeper in Presidio, said he remembers his father telling of the shells falling near the first Spencer store. Small arms punctured the store's kerosene storage tank.

"Presidio was much closer to the river then," Spencer explained. "The town site was moved back from the river after a bad flood in the "20's."

Americans sent a note to Villa's artillery commander asking that the gun's elevation be lowered. It was done so immediately.

But when the artillery was adjusted, some of the shells then fell among Villa's own men, Cabrajal recalled.

"Several men near me were blown to bits when a shell landed close by," he said.

The final battle, fought during the late morning hours and early afternoon, lasted only a few hours.

The federals, outnumbered 5 to 1, retreated to the river and crossed over, only to be rounded up by U.S. cavalrymen from Marfa, sent to protect Presidio.

Villa lost an estimated 100 soldiers in the final assault. Some historians have put the Villa dead at a much higher figure. But Cabrajal said losses were light on the final day.

"The Federalists lost heavily in the last attack," Cabrajal said.

Rodriquez, one of the federal soldiers to escape to Presidio, was put into a camp with other soldiers. Their arms, munitions and other supplies were taken over by the U.S. Army.

Cabrajal said the chaparral area was littered with destroyed, dead horses, bodies of dead and wounded.

"The wounded were cared for by several doctors in the Villa army," he said. "Many of the wounded, both Villa and army men were carried to Presidio for treatment."

Cabrajal said after the town was taken, the Villa troops sacked homes for food, clothing and gold.

We just stayed around the town for about a week before leaving, he said.

During the week after the battle, townspeople were told to bury the dead. Some of the federal troops, watched carefully by Americans ordered to protect them from the Villistas, also helped bury the dead.

Cabrajal said most of the Villa men just rested, drank and ate while the townsmen cared for the dead and wounded. Equipment left behind was quickly collected for Villa's rag-tag army.

Rodriquez walked to Marfa with the thousands of refugees, where all were put aboard trains and sent to Fort Bliss. He stayed in the United States and worked on the Southern Pacific Railroad after the revolution until 1926. he returned to Ojinaga and worked as a laborer.

Cabrajal fought two more years with Villa. He was seriously wounded in a battle on the Durango-Chihuahua border in early 1916. He finally returned to the Ojinaga area about 1920. He lives with his sons. Rodriquez lives with his daughters.

The men said there were several Ojinaga residents who fought in the battle, but most are now gone. Occasionally, Cabrajal and Rodriquez talk over the fight with these few surviving friends.

Both said they wouldn't fight again if they had their lives to live over.

"We did not get anything out of the battle, except to nearly get killed," Cabrajal said.

Rodriquez said the fight came about over politics.

"There was no other way except to do battle," explaining why the political fight ended in bloodshed.

"There were no speeches" just fighting, he continued. Cabrajal said he has no interest in politics.

"We don't dedicate ourselves to parties anymore," he explained.

[ view entry ] ( 4982 views ) | permalink |

Check out this Candelaria bridge video just posted on utube from Drlabash:

[ view entry ] ( 4820 views ) | permalink |

SENORA VILLA SAYS OF PANCHO: POOR PEOPLE ARE THE ONES WHO LOVE HIM. A PEN FROM THE PAST BY ROSS MCSWAIN

In mid-October 1965, a new mayor took office in Ojinaga, just across the river from Presidio. A gala fiesta was planned for the change in municipal officials. Dignitaries from all over the state of Chihuahua were on hand for the event.

But probably the most important person there was Luz Corral Villa, a spry 72-year-old matron with shining eyes, steel gray hair and a broad smile. Luz Villa is the widow of Pancho Villa, on of the most famous men in Mexico. Although more than 50 years ago Villa's army of peasant soldiers sacked Ojinaga after a bloody battle in which mort than 1,000 persons died violently, Senora Villa was given one the biggest welcomes any VIP could receive from Ojinaga citizens.

What was the secret of Senora Villa's acceptance, not only in Ojinaga but in cities though out the United States, including Columbus, N.M., where Americans died before Villas guns?

"The older people remember what Pancho Villa did for the poor." Senora Villa said, "Even though there was much bloodshed many years ago, the poor classes still remember him as their hero, their Robin Hood."

Senora Villa, a resident of Chihuahua City, was the revolutionary's only legal wife. (Note: According to the New York Times of July 13, 1966 Soledad Seanez Holguin also legally married Villa on May 1, 1919)

She readily admits that Villa had many mistresses and sired some 15 children by different women by several women, her eyes sparkle as she speaks of the bandit-general's exploits and their brief and hectic married life.

Senora Villa maintains a Pancho Villa museum in Chihuahua City. She lives in the same house Villa bought in 1906 from the money taken in bandit raids.

The 50-room house has been rebuilt twice since it was purchased. It was destroyed during the Mexican Revolution in 1913 and during the war between Villa and Carranza in 1917.

"Pancho didn't especially like politics," Senior Villa said during an interview in Ojinaga. "He had a strong sense of loyalty to the poor. He was pushed or forced to take part in the revolution," she said.

During the height of Villa's successes when he was undisputed dictator of all the northern provinces of Mexico, Senora Villa lived in seclusion in El Paso.

"I saw my husband for several days each month during the revolution when he would sneak into El Paso," she said. When he and Carranza fought, Pancho sent me to Havana, Cuba for safety."

Senor Villa was in Havana during the last revolutionary struggle. Her home in Chihuahua City was destroyed a second time.

When the Columbus, N.M. raid was staged in 1916, Villa had just sent his wife to Havana.

"I knew he was planning to attack an American town, but I did not know where or when," she said recently. "Pancho was furious with President Wilson for stopping the shipment of arms to him. He felt that the American president was in agreement with his actions. The raid was a retaliation for President Wilson's arms emabargo."

Senora Villa said stories saying Pancho Villa was not at Columbus during the raid are not true.

He planned and led the raid, she said, even though he was advised by his generals not to do so. They told him the American soldiers would follow and destroy him but he would not listen.

Senora Villa said her husband was very hot-tempered but was not cruel.

"He despised cowards and incompetent offices."

Villa hanged hundreds of persons in Durango and Chihuahua accused of desertion from his peasant army. Historians note, too, he had numerous officers in his band shot for failing to carry out his orders.

"The poor people are the ones who truly love him and his memory," she said. "Others hate and despise his name."

Senora Villa said her husband never drank to excess.

"He enjoyed parties" and found many beautiful women at the gatherings. He was famous. Women threw themselves at him," she added, explaining his many love affairs and many children."

The bandit's wife reared five of the reported 15 children born to various Villa mistresses. Three of his daughters and two sons are still living. A son, Samuel Villa, still resides in Chihuahua City. Octavio Villa, a minor government official, was killed at an ambush at Matamoros about two years ago. Another son, Agustin Villa, is in a mental hospital in Los Angeles. A nephew of Villa's, his namesake, fought in World War II with the U.S. Army. He was a paratrooper, Senora Villa said. The nephew now lives in Los Angeles.

Villa and Luz were married in 1911 when she was l8 years old. They met in 1910 when he took over her hometown of San Andres. He was a bandit chieftain, she said.

Senora Villa was living in Chihuahua City when Villa was gunned down in an ambush near Parral, Chihuahua, a mining center. His ranch, called Canutillo Hacienda, was near Parral but in the state of Durango.

"The ranch was taken by the government", she said, "because Villa was accused of owing the government more than $80,000 in taxes."

The revolutionary's widow said tales of Villa treasure being buried in the Sierra Madre Mountains is false.

"If there had been a lot of treasure he would not have had to ask for so many loans."

"The money taken from banks during the revolution went for and ammunition, uniforms and other equipment," Senora Villa said, "He was always in need of money for ammunition. During the last days of fighting, he had to ay two and three times for it (munitions) than its actual price since most of it had to be smuggled into Mexico."

In 1922, a year before he was killed, Villa was approached by an American film company about appearing in a motion picture about his life.

"Pancho refused to take part in the picture unless the company could promote the construction of a school in corporation with the Mexican government," Senora Villa said.

The school, to be used by orphans, was rejected by the Mexican government. No reason was given for the refusal, even though the school was badly needed.

The famous bandit loved children, his wife said.

"Pancho used to pick up children off the streets and take them to school. He took 300 children and fed them and bought them clothes at one time in Juarez."

Pancho and Luz Villa had a baby girl about a year after their marriage, but the infant died.

"I would have been proud to have had her live," Senora Villa said.

In 1950, Mexican president Aleman made an offer to rebuild the Villa home in its original state but nothing ever came of the offer. Senora Villa, however, has restored the home out of her funds, raised though donations to her Villa museum.

She lives alone in Chihuahua City, except for several servants who also help maintain the museum.

Last August and September, more than 3,000 persons visited her home to see the large collection of Villa papers, uniforms and other personal items of the late revolutionary.

On display is the Dodge touring car in which Villa was riding when shot to death, battle flags, weapons of all kinds, uniforms, his desk, letters and other numerous items.

Senora Villa said she had ten volumes of registration books containing more than of visitors to the museum.

"Guests have come from all over the world," she said.

Senora Villa is also a traveler. She has been all over the United States and has made several jet flights.

Early in 1965, she toured the U.S. appearing in person at premier showings of a documentary film on Villa made during the revolution. The film, put together from silent newsreels, but narrated, was produced by Columbia Pictures, Inc. The film company paid Senora Villa's expenses on the journey.

She said she tries to make several trips a year to Juarez. Her recent trip to Ojinaga was the first such trip in years. She was a houseguest of Mr. and Mrs. Pete Valenzula who she met in Chihuahua City about 12 years ago. Valenzula is a clerk in the Spencer Store at Presidio and has lived in the immediate area since birth.

Senora Villa's best friend and traveling companion is Senora Margaret H. Campos, a Chihuahua City music teacher. They have been friends for more than 40 years.

Villa's wife's greatest wish is that Pancho could have lived out his life more peacefully.

She said he was a happy man, although he was virtually in exile on his Durango ranch.

He was a big man, standing about six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds. He was graceful in his movements, and had a commanding voice. His very being expressed confidence.

"He had a strong sense of loyalty to the poor," she said. "He knew the hardship of being a field-hand, a laborer. He only wanted the poor to have more to eat, better living conditions and better education. These things he and his family had done without."

In April, a highlight of Senora Villa's life came when Governor Campbell of New Mexico visited her in Chihuahua City to discuss plans for the extension of U.S. Highway 180 from Columbus, N.M. into Mexico and into the state of Durango. The scenic highway Federal Road 45 in Mexico, would be called the Pancho Villa Trail. The highway should be an international effort.

Mexican peasants still call Pancho Villa, "mucho hombre." He will always be "a big man" to Luz Villa, his wife. Pancho Villa died on a hot July afternoon in 1923 as he and four bodyguards traveled a dusty road outside Parral.

More than a dozen heavily armed men blasted the Villa car as it started over a bridge crossing a shallow ravine. The gunmen, believed hired by Mexico City politicians, had hidden in ambush in a deserted adobe house.

Senora Villa said she did not know who killed her famous husband. She suspects he was assassinated by political foes.

"He was being mentioned too much in the news," she said. "He didn't like the way the government under Obregon was being run and said so on a number of occasions. He was killed because the politicians suspected he was being urged to lead another revolt."

Luz Villa's husband died as he had lived violently and with a pistol in his hand.

"He trusted the government when he was granted the pardon. But they (the politicians) apparently didn't trust him," she said.

Thanks Ross for the fine article, a chance for us all to look back and ponder. Gj

[ view entry ] ( 6502 views ) | permalink |

UPPER WALKER CREEK

UPPER WALKER CREEK

UPPER WALKER CREEK

UPPER WALKER CREEK

CAPOTE CREEK

CAPOTE CREEK

In the last 24 hours some 2 inches of rain has fallen in Candelaria and the ranches to the north in the Sierra Vieja. Walker Creek and Capote Creeks are running fast and according to reports, the Rio Grande is out of its banks at Candelaria. Candelaria lies in a natural flood plain and is subject to severe flooding when rain falls in the Sierra Vieja.The first two crossings of Capote above Candelaria are impassible. We are marooned.

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 7688 views ) | permalink |

ABOVE IS THE BRIDGE ON 3-22-08

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICE

ABOVE IS FORMER BRIDGE SITE ON 3-24-08

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICE

PHOTO COURTESY CLARA LONG@BORDER STORIES.ORG

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICE

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICEYesterday after I posted the article and photos of the bridge, a large contingent of Border Patrol trucks and personnel removed the Candelaria footbridge. It no longer exists. As soon as we learned of the removal, we drove to Candelaria arriving there about 10:30 am. The last of the Border Patrol trucks were just leaving and the road blocked by heavily armed but courteous BP guards. I ask if the bridge was gone and if I might go take some photos at the crossing. They let us pass after the last truck drove out of the bosque. The bridge is gone. Not even a scrap or tiny piece of it left on either side of the river. Across the river on the Mexican side, a few amazed locals waved back to us. It was swift and efficient removal. Yesterday, it was there, today it is gone. They hauled every piece of the old bridge out on a flat bed trailer. As we drove by the school, the entire schoolyard was crammed full of Border Patrol vehicles. The remains of the bridge sat encircled on the trailer by U.S. government vehicles. We decided it was time to go home. It is a sad day on the river. For more than 50 years, the little bridge stood as a symbol of cooperation between two tiny Texas-Mexican border villages. Now it is history.

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 4446 views ) | permalink |

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICE

PHOTO BY GLENN JUSTICE

PHOTO COURTESY CLARA LONG@BORDERSTORIES.ORG

The old Candelaria bridge is still here. It spans a muddy trickle some five-foot wide in an almost dry arroyo. It's hot in the Presidio Valley. Few venture outside after the cool morning hours. The school kids are out for the summer so they are not using the bridge. Few do these days. Everyone waits to see if the bridge will survive. A squad of Border Patrol men and women stationed at the Candelaria school go about their duties patrolling this part of the border. It's a thankless job and they are the only law we have here. Some Andrew Jackson art painted on an old car hood expresses a lot of feelings about the school being closed. Across the river at the medical clinic, Dr. Maribel Aquino waits and wonders if her link to the outside world will be cut by the removal of the bridge. Manuel Carrasco is doing well and just got his new work visa. Not long ago, Manual suffered a heart attack on the Texas side and thanks to Dr. Aquino's clinic in San Antonio is alive and well today.

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 5551 views ) | permalink |

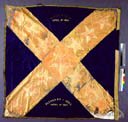

Above are four Texas Confederate battle flags from the Texas State Archives.

Truth is, the thousands of fine, brave Texans who fought and died in the Civil War did not fly the red, white and blue stars and bars of the south into battle. They did not fight to keep their slaves because few owned slaves. Texans joined the Confederate cause and fought and died in most of the major battles of the war. They fought and died because they felt threatened by the Federal Government and the election of Abraham Lincoln.

For more see:

http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/treasures/fl ... flags.html

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/onli ... /qkh2.html

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 85858 views ) | permalink |

Glenn Willeford and Gerald Raun have done an insightful study of Big Bend cemeteries. Their "Cemeteries and Funerary Practices in the Big Bend of Texas, 1850 to the Present" is 240 pages packed full of out of the ordinary tidbits of information that genealogists or anyone interested in finding the grave site of a long lost relative will want to read. While many parts of the country have readily available listings of local graveyards and their residents, final resting places in the Big Bend has been a long overlooked topic.

Willeford and Raun did not simply republish courthouse records but did extensive research of the some 63 graveyards in the Texas Big Bend and personally visited each of them. Many of these isolated family cemeteries have escaped official records in Brewster, Presidio and Jeff Davis counties and the book finally documents these historic gravesites. Included are 42 photographs of various cemeteries as well as detailed locations.

Glenn Willeford is an American writer and professor of history who lives in Chihuahua. In 2004, his first novel, "Red Sky In Mourning" became the first English language book published by Universidad Autonoma de Chihuahua. A follow up to Red Sky titled "Passage to Lisbon" is now in the works. Gerald Raun, Ph.D, is the author of four books including the first "Snakes of Texas" offerings and over fifty journal articles on biology and history. "Cemeteries and Funerary Practices" is available at Front Street Books in Alpine. Email Front Street at findit@fsbooks.com or call 432-837-3360.

Also see: http://www.fsbooks.com/books/books.html#willeford

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 4882 views ) | permalink |

<<First <Back | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | Next> Last>>