TO MY READERS: HOW TO USE THE BLOG

Click Here

My friend Lonn Taylor published an article in the Big Bend Sentinel about the Porvenir archaeological dig titled "Uncovering The Truth About The Porvenir Massacre".

Read it at:

http://bigbendnow.com/2016/01/the-rambling-boy-96/

Thanks Lonn!

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 3068 views ) | permalink |

Marfa Public Radio recently did interviews and an article about the Porvenir Massacre archaeological investigation. Check it out at: http://marfapublicradio.org/blog/a-new- ... e-of-1918/

Be sure and click on the adobe acrobat best price audio link for the whole story.

Many thanks to Tom Michael!

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 3108 views ) | permalink |

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Photo by Jessica LutzOne January night in 1918 a mass murder took place in far northwest Presidio County, Texas. It happened not far from a tiny, little known village called Porvenir. In Spanish, Porvenir means future however there was no future for the some 140 Mexicans living there at the time who subsisted by farming, raising goats, sheep, a few cattle and horses, casino canada. They lived in crude huts called jacales constructed with stone or adobe walls and thatched roofs of ocotillo. While some were U.S. citizens many of the residents of Porvenir came to Texas trying to escape the terrible civil war that consumed Mexico during those years. Porvenir had a school and a cotton gin but no store and the nearest church was located just across the Rio Grande in nearby Pilares, Chihuahua.

Beginning in 1910 and lasting for a decade, the Mexican revolution created havoc in Mexico as well as along the Texas and New Mexico border. As many as a million people lost their lives or simply disappeared during this war. Bandit raids along the border became more and more common. On March 9, 1916 Pancho Villa led some 500-mounted horseman in an attack on Columbus, New Mexico that killed 18 Americans and left the business district of the little town in ashes. As a result, President Woodrow Wilson ordered General John “Blackjack” Pershing and four regiments of cavalry supported by two regiments of infantry into Mexico to kill or capture Villa. The expedition ended in failure about a year later after the elusive Villa simply vanished into the Sierra Madre. A few months after the Columbus raid President Woodrow Wilson deployed more than 100,000 National Guard troops to guard the Mexican border. On May 5, 1916 as Pershing’s army hunted for Villa another group of bandits attacked Glenn Springs, Texas located in today’s Big Bend National Park. The raiders killed three troopers of the Fourteenth Cavalry and a four-year-old boy and set Glenn Springs ablaze. On Christmas Day, 1917 some 45 raiders thought to be Villistas attacked the Brite Ranch located near Capote Mountain in western Presidio County. They looted the Brite store and hung mailman Mickey Welch from the rafters before cutting his throat to make sure they had killed him.

All of this violence spread terror among Big Bend residents. Large numbers of people left their border homes seeking safety in Marfa and other west Texas towns. There were heated demands for retaliation. Sadly these demands for vengeance developed into reality and revenge descended upon the people of Porvenir who had nothing to do with any of these raids. Shortly after after midnight on January 28, 1918 some forty U. S. cavalry troopers of Troop G, Eighth Cavalry commanded by Captain Henry H. Anderson along with about ten or more Texas Rangers and a group of ranchers surrounded Porvenir in the darkness of a freezing cold night. Some of the ranchers wore bandanna masks to hide their identities as they awoke the townspeople and ordered everyone outside where someone built a fire. According to several witnesses, the soldiers sat atop their horses and did not dismount simply sitting around the village so no one could escape. The Rangers started separating the men from the women.

They selected 15 men and boys with ages ranging from 16 to 72 years and marched them off into the darkness. Not long after this many gunshots rang out in the darkness as the fifteen victims were shot to death without ceremony. The sound of gunfire produced instant pandemonium in the village as the survivors in the village realized that something dreadful had taken place. Fearing the worst no one dared to venture out into the darkness to see what had happened. Sometime before dawn thirteen-year-old Juan Flores made his way to school master Harry Warren’s house north of Porvenir to report the shooting. Young Flores was lucky to be alive. Someone grabbed him the night before and shoved him into to the group to be killed. But a rancher said the Flores boy was too young and somehow got Juan released before the killing took place. The following morning Juan accompanied the schoolmaster to a place south of Porvenir until they came across a pile of bodies guarded by the soldiers. It was a ghastly scene. According to Juan Flores, the bodies appeared to have been tied together and shot so many times they appeared to have been purposely mutilated. Juan saw his father’s body. Longino Flores was almost unrecognizable to his son since part of the man’s head had been blown away. At some point that morning an old woman crossed the Rio Grande from Pilares driving a cart. The soldiers helped her load the bodies on to the cart and she took them to Mexico where they were buried in a mass grave in the Pilares churchyard.

Above is photo of Pilares, Chihuahua graveyard where Porvenir massacre victims were buried in a mass grave.

Photo by Jessica Lutz

The survivors fled the place, some going to Mexico and other locations. A few days after the massacre, a contingent of troopers from Camp Evetts came to Porvenir and knocked down and burned the abandoned jacales the people of Porvenir once called home. The village ceased to exist.

Texas Ranger Captain Monroe Fox commander of Ranger Company B attempted to whitewash the massacre waiting some three weeks before he even filed a report of the event. The captain claimed his men had gone to Porvenir in search of bandits and when they arrived came under fire from the brush. They returned fire and the next morning found fifteen dead bodies. Captain Anderson of Troop G Eighth Cavalry reported that his men came upon the bodies the morning after the massacre and had no idea how they had been killed. A few, very few newspaper articles about the massacre ever went to press but in June 1918 Governor William B. Hobby fired five of the rangers who had been at Porvenir and disbanded Company B. Captain Fox and several other rangers resigned but no criminal actions were ever taken against anyone for the crime.

Glenn Justice started researching the story of the massacre in the late 1980’s and presented a paper about it about it to the West Texas Historical Association before publishing his book “Revolution On The Rio Grande” that included a chapter on the massacre in 1992. My research took me as far as the National Archives in Washington D. C. and Suitland, Maryland where Justice used the Freedom Of Information act to obtain vital previously classified army documents about the massacre.

Slowly the paper evidence concerning the massacre grew to the point that it left little or no doubt that the massacre had actually taken place and who had been involved. Only one vexing question remained; that being who had actually done the killing the fifteen that tragic night? Then in the spring of 2002 Justice learned of a Porvenir survivor still living. His name was Juan Flores. At that time Mr. Flores was ninety-seven years of age but in good health and his mind still sharp. Remarkably, he did not even tell his family about the massacre until his last years. Mr. Flores suffered from terrible nightmares about the massacre that his family could not understand. Finally he decided to tell the story of what he had witnessed that awful night. In November 2002, Mr. Flores made a journey to Porvenir massacre site and revealed to those present the exact place where the killings took place. Remarkably some cartridge casings still lay on the ground and metal detectors indicated the presence of many more at the site. Justice picked up a few and over the next decade returned to Porvenir many times after that and each trip found more and more cartridge cases, bullets, bullet fragments and other artifacts.

In 2015 former Texas Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson and Austin lobbyist Lee Woods offered their help with the Porvenir project. All ll felt it important that the little known Porvenir massacre story deserved being told and it would make a great topic for a documentary film. But, at the same time, realized that in order to accomplish this archaeological work had to be done at the massacre site. Also it was necessary to shoot at least enough video to put together a documentary film trailer to help us raise money to fund the project. Archaeologist and historian David W. Keller had long been familiar with the work at Porvenir and kindly agreed to help us assemble a team to investigate the site. David headed up the archaeologists who agreed to help with the work including Sam Cason, Tim Gibbs and Amber Harrison.

David Keller examines artifacts

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Glenn Justice, Jerry Patterson and David Keller

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Filmmaker Ford Gunter videos archaeologists at work

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Sam Cason pilots his drone making photos to be used for high definition maps

Photo by Jessica Lutz

In addition to being an archaeologist, Sam has expertise doing photographs with aerial drones that will prove to be most helpful in mapping some fifteen acres surrounding the massacre site. With the drone and the high-resolution photos it could make would allow us to map the location of each of the artifacts that were found. The archaeologists also planned an intensive five-acre metal detector survey on foot around the site. We employed the services of filmmaker Ford Gunter and his assistant Patton Baker to film archaeological work at the site, do interviews and also shoot aerial footage of the massacre site as well as the village of Porvenir and surrounding countryside.

Stanley Jobe pilots his helicopter while Ford Gunter shoots video

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Stanley Jobe of El Paso was kind enough to provide a helicopter to do our aerial filming. On Friday, November 20, 2015 the Porvenir expedition set out for the site of the massacre. Because of the extremely remote location we had to camp for the next three nights. A cold front blew in and the first two nights plunging temperatures into the high 20’s with high winds. At first the expedition members didn’t think the helicopter could even fly in such conditions but fortunately by Sunday the weather cleared and could not have been nicer.

Photo by Glenn Justice

One of the .45 Colt bullets found at the massacre site

Photo by Glenn Justice

A 30.06 case along with assorted .45 bullets discovered at the massacre site

Photo by Glenn Justice

The archaeologists unearthed 27 new artifacts, mostly bullets, bullet fragments and cartridge casings. Up to that date, I previously found 21 artifacts giving us a total of 48 artifacts. The cartridge cases and bullets found came in a number of calibers including 30.06, .45 Colt, and .45 acp. The head stamps on the cartridge cases are dated and most were manufactured by two United States Army ammunition manufactures. Some were made by the Frankfort Arsenal of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania that made ammunition for the U.S. Army from 1816 until it closed at the end of the Vietnam War. Other cartridge cases found at the massacre site had been manufactured by the Union Metallic Cartridge Company a division of Remington Arms that made rifle and pistol ammunition for the U. S. Army from the time of the Civil War. The head stamp dates on all of the ammunition ranged from 1909 to 1917. It should be noted that guns carried by most Texas Rangers during the time of the massacre were revolvers chambered in the .45 Colt caliber and 30-30 Winchester saddle guns. No .30-30 cartridge cases or bullets were found at the massacre site. Some U.S. Army troopers carried .45 caliber revolvers but generally the 1911 Colt Automatic Pistol were carried mainly by officers since the weapon was in short supply during the World War I years.

Jerry Patterson photographs artifacts while Steve Anderson and Glenn Justice look on

Photo by Jessica Lutz

Overall everyone who took part in the archaeological work at Porvenir considered the finds to be exceptional. Principle archaeological investigator David Keller summed up the project “Considering that I was skeptical that we would find additional materials, I was pleasantly surprised by the volume and consistency of our finds. The intensive survey also revealed a highly patterned artifact distribution. I can say with a fair degree of confidence that the artifactual distribution, the types of artifacts, all strongly conform to the hypothesis that this was the site of the Porvenir Massacre of 1918. The findings also strongly implicate the U.S. Cavalry.” Our next step is to have the artifacts carefully examined by an expert skilled in ballistic analysis.

Glenn Justice

[ view entry ] ( 931 views ) | permalink |

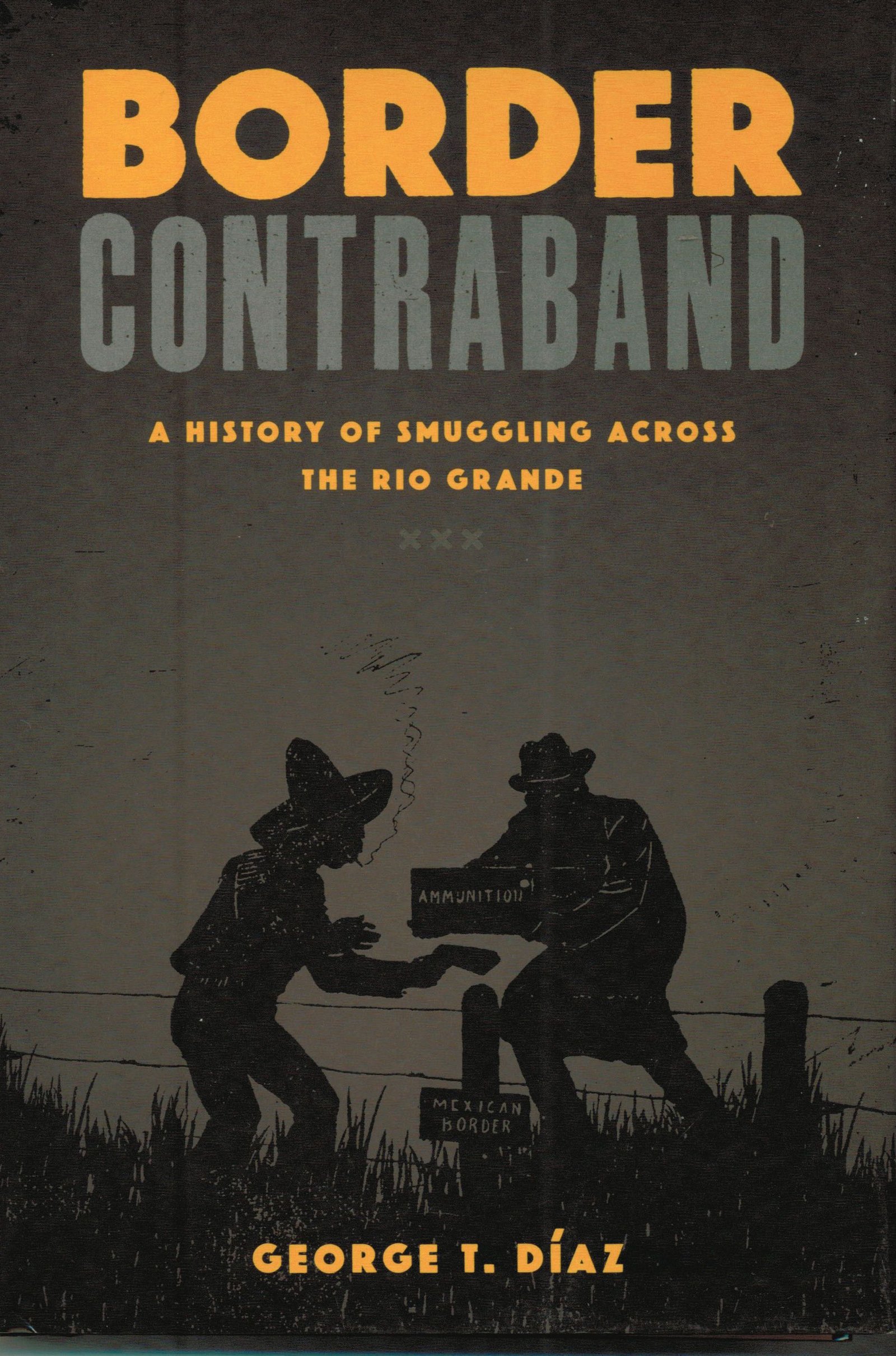

Border Contraband: A History of Smuggling Across the Rio Grande By George T. Díaz (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015, 228 pages, maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, ISBN 978-0-292-76106-3, hardcover edition $45.00.)

Professor George T. Díaz of Sam Houston State University offers a well researched historical study of smuggling along the Texas-Mexican border. The work focuses on Laredo, Texas as well as its Mexican sister city across the Rio Grande, Nuevo Laredo. The author points to the importance of the two Laredos with Nuevo Laredo being the third largest port in Mexico and Laredo, Texas the number one inland entry port on the U.S.-Mexican border. The vast Pan American Highway system runs through both ports and Laredo, Texas today is situated on the southern end of Interstate 35. Since 1882 Laredo, Texas has been linked by railroad service making its location ideal for anyone, including smugglers, who wish to travel throughout the United States or Latin America. Díaz did well choosing this location for his research.

Smuggling on the Texas border is a worthy historical topic but one not previously given a great deal of attention largely because of the illegality of the subject. Also, it is one not easily researched because of this unlawfulness. The author breaks his work into three time periods beginning in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War and designated the Rio Grande as an international boundary. Professor Díaz details this first period that ends with the outbreak of the Mexican revolution in the first decade of the twentieth century as a time in which both Mexican and U. S. customs enforcement concentrated on the collection of tariffs needed provide essential revenue to both countries. The author points out the attitude of border residents during these years as being a tolerant acceptance of smuggling. This began to change with the coming of the railroads in the 1880’s that spurred population growth particularly on the Texas side. The outbreak of civil war in Mexico in 1910 brought violence with enforcement of arms and ammunition embargos imposed to stop the southward flow of the weapons of war into Mexico from the United States. U.S. Customs agents, once primarily collectors of revenue, found the enforcement of neutrality laws designed to keep illegal arms out of Mexico a very dangerous business.

The author does not ignore abuses during the era of prohibition when Customs agents and Texas Rangers resorted to ambush and murder of armed tequileros (tequila smugglers). By 1928, the two Laraedos became a transit point for drug traffickers who took up the smuggling of opium because it could be easily concealed in automobiles and in various types of shipments. Díaz makes use numerous case studies to illustrate his points. The professor’s research is thorough and innovative. He presents an impressive bibliography of archival and manuscript collections as well as scholarly articles and secondary sources. He also uses Mexican corridos (songs as sources) to broaden the readers understanding. It is a work well done and worthwhile.

Glenn Justice

[ view entry ] ( 3835 views ) | permalink |

Check out this link for a short video about Quanah Parker's star house:

http://www.voanews.com/content/comanche ... 96109.html

Gj

[ view entry ] ( 3231 views ) | permalink |

Dear Friends and Members of the Quanah Parker Trail:

Please find below and attached information regarding the steps now being taken to address the deteriorating condition of Quanah Parker's "Star House." Holle Humphries of the Quanah Parker Trail steering committee had forwarded the information regarding the most recent meeting on August 29 as a follow-up to the first meeting in June. One of the individuals figuring prominently in some of the preliminary preservation survey work of the "Star House" is our own Dr. Elizabeth Louden of Texas Tech University who has also been an active contributor to historic preservation efforts with the Texas Plains Trail region and affiliates such as Sammie Simpson and others.

If you have any follow-up questions regarding the current project please address those to Holle Humphries of the QPT steering committee.

Best wishes, tai

Tai Kreidler

Quanah Parker Trail Steering Committee

http://www.quanahparkertrail.com

806-224-3133

[cid:image002.jpg@01CE0F86.002D82E0]

It's Good That Way, Don Parker

From: Holle Humphries [holle_h@att.net]

Sent: Tuesday, September 01, 2015 12:06 AM

Subject: Report: Comanche Nation's "Save the Star House" meetings: 1. June 20, 2015; 2. August 29, 2015

Dear Quanah Parker Trail Steering Committee,

This is a report for you of this summer's two events surrounding the initiative launched by Wallace Coffey, Chair of the Comanche Nation, to save Quanah Parker's "Star House" from total deterioration.

The good news is that apparently, our efforts to create the Quanah Parker Trail throughout our region as a non-profit entity commemorating places and events in Quanah's life and that of The People, all undertaken with research, dignity, and respect, have gained the nod of the Comanche Nation's administrative leadership in this regard, as Wallace Coffey asked Ardith Parker Leming to see that a representative of the QPT was invited to the Star House proceedings.

Wallace Coffey called two meetings of all interested members of the Parker family and representatives of organizations affiliated with the interests of the Comanche Nation to bring them together on the grounds of the Star House to discuss possibilities for saving it from ruin.

The Star House has suffered years of weathering, with the final blow delivered this spring by 4-foot floodwaters that filled it as high as the electrical switches mounted on its interior walls.

Owing to the nature of its condition, inciting alarm in all who have witnessed its current state, these meetings were called to be convened on June 20, 2015, and August 29, 2015.

In doing so, Wallace Coffey has commendably utilized his considerable clout as a leader to bring together previously fragmented factions and groups of people inside and outside the Comanche Nation by enjoining them to join together in a last collective effort to save the Star House.

This is history resonating in our time on multiple fronts.

Wallace Coffey himself is descended from the formidable, notable and mighty Ten Bears (c. 1790 - 1872), a significant Comanche principle chief of the Yamparika band in the nineteenth century and a war chief whose warriors counterattacked Kit Carson to drive off his men after the First Battle of Adobe Walls in 1864.

Ten Bears repeatedly met toe-to-toe with the U.S. government at the treaty table and in Washington D.C. in a heroic effort to stave off encroachment on Indian lands, efforts that ultimately ended in futility, owing to the Zeitgeist of Manifest Destiny driving U.S. government policy during that time at the expense of all its indigenous First People.

Ten Bears is known famously for his eloquent speech delivered at the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, decrying the U.S. government's efforts to force Indians who had lived and roamed freely throughout the continent onto the confined boundaries of reservation lands.

Following the leadership legacy of his great-great-grandfather, Wallace Coffey decided this summer to bring together The People in a collective effort to resurrect the Star House and save it from ruin.

He stated he wanted to this effort to rank as one among others to stand as his historical legacy left for the generations of those to come after him.

Ardith Parker Leming telephoned in early June and said that Wallace Coffey had asked her to contact the Quanah Parker Trail and Texas Tech University, and Parker family members to ask them to come to a meeting to discuss the fate of the Star House.

Ardith, like her great grandfather, Quanah Parker, also is a leader. And so she contacted them all, and so we all went.

First meeting: June 20, 2015:

Attended by over two hundred people, this first meeting provided Wallace Coffeey with the affirmation he needed from Parker family descendants and the leaders and people of the Comanche Nation to signify that all were willing to work together to surmount any political challenges posed in the past and join in a new collective effort to stabilize and hopefully eventually restore the Star House.

After the meeting, U. S. Army Ft. Sill Garrison Commander Col. Glenn Waters escorted visitors via automobile caravan to the original site of the Star House. In anticipation of doing so, Col. Waters had re-graveled the road leading to the original property site.

Despite the tall grasses, tribal members located on the Star House original grounds, the original well and the cement foundation for the windmill, that had been impressed with the mark of Quanah's brand.

This first meeting was reported in the news media, and concomitantly, the New York Times ran an article about its current deteriorated state.

2. Second meeting: August 29, 2015:

At this meeting, Wallace Coffey reported that:

a. Legal paperwork had been submitted as of the past week to create a 501c(3) non-profit entity for "Save the Star House", w/ legal status hopefully to be confirmed soon.

b. Several agencies were working to combine efforts and expertise to assist in assessing the condition of the Star House, so that projections can be made as to what needs to be done to first stabilize and then possibly restore it, and how much money needs to be raised to achieve such goals. These agencies include:

-- National Trust for Historic Preservation

-- Preservation Oklahoma

-- the State Historic Preservation Office

c. Under the auspices of the Comanche Nation and advising agencies (cited above), the TAP architectural firm, noted for its preservation work, had been contracted and paid by a grant to assess the current condition of the Star House.

The lead architect of the TAP firm gave the report of the firm's assessment, and distributed comprehensive documentation profiling the assessment made, to the audience.

It is estimated that $220K is needed for immediate stabilization; it is as yet undetermined how much $$ will be needed to restore the house in its entirety.

d. Benny Tahmahkera, direct descendant of Quanah Parker, performed a 10 minute monologue summarizing the history of the Star House.

This Comanche White House West of the Mississippi hosted within its walls such illuminaries and former adversaries as well as allies of Quanah Parker to include: President Theodore Roosevelt; British Ambassador Lord Brice; Commissioner of Indian Affairs Robert G. Valentine; U.S. Army Generals Hugh L. Scott, Nelson Miles, and Frank Baldwin, all of whom had fought Quanah and his Indian allies in the Red River War; ranchers Charles Goodnight, Samuel Burk Burnett, Tom Burnett, and Dan Waggoner; and many historic Indian chiefs of the time, to include Geronimo (Apache), Eschiti (Comanche), Lone Wolf (Kiowa), and American Horse (Sioux), to name a few.

3. Future PR efforts:

Donna Wahnee, Director of Special Projects for the Comanche Nation, reported that several events are in the works to profile the efforts to "Save the Star House."

There are hopes and plans for the Chair to travel to Lubbock for the Cowboy Symposium, and as well to Quanah, TX; Fort Worth, TX; and other destinations, as well as to work with civic and historical groups such as the West Texas Historical Association, to publicize the efforts and promote fundraising endeavors to save the Star House.

Noted asides:

A. In a private conversation with Johnny Owens, Comanche County Commissioner, he acknowledged that he is aware that there is a need as well to consider flood control for the future, as the Star House is located in a 100-year flood plain. This is indeed important.

B. It should be of interest to the QPT Steering Committee to note that one of architectural firm's staff members in private conversation with Tai Kreidler, QPT SC member, noted the importance of Tai having earlier referred Dr. Elizabeth Louden of the TTU architectural faculty to execute a laser scan of the entire structure, previously.

The house has deteriorated considerably since then, and her laser scan provides to architects an important resource of data regarding the structure of the building.

In closing:

Here are URLS from two media sources that profiled stories about the Star House:

http://www.kswo.com/story/29611274/coma ... star-house

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/19/trave ... .html?_r=0

See the PDF file attached that summarizes the Comanche Nation's "Save the Star House" efforts.

See attached: a few photos taken at the June 20 and August 29 meetings.

Sincere regards,

Holle Humphries

[ view entry ] ( 3374 views ) | permalink |

Finding the Great Western Trail by Sylvia Gann Mahoney

Foreword by Ray Klinginsmith

History / American West

Grover E. Murray Studies in the American Southwest

6 x 9, 304 pages; index

60 halftones; 12 maps

$34.95 hc 978-0-89672-943-8

E-book available

October

The Great Western Trail (GWT) is a nineteenth-century cattle trail that originated in northern Mexico, ran west parallel to the Chisholm Trail, traversed the United States for some two thousand miles, and terminated after crossing the Canadian border. Yet through time, misinformation, and the perpetuation of error, the historic path of this once-crucial cattle trail has been lost. Finding the Great Western Trail documents the first multi-community effort made to recover evidence and verify the route of the Great Western Trail.

The GWT had long been celebrated in two neighboring communities: Vernon, Texas, and Altus, Oklahoma. Separated by the Red River, a natural border that cattle trail drovers forded with their herds, both Vernon and Altus maintained a living trail history with exhibits at local museums, annual trail-related events, ongoing narratives from local descendants of drovers, and historical monuments and structures. So when Western Trail Historical Society members in Altus challenged the Vernon Rotary Club to mark the trail across Texas every six miles, the effort soon spread along the trail in part through Rotary networks from Mexico, across nine US states, and into Saskatchewan, Canada.

This book is the story of finding and marking the trail, and it stands as a record of each communities efforts to uncover their own GWT history. What began as local au.pills.com bravado transformed into a grass-roots project that, one hopes, will bring the previously obscured history of the Great Western Trail to light.

Sylvia Gann Mahoney was an educator for thirty-three years at community colleges in Texas and New Mexico as an administrator, teacher, and rodeo team coach. In 2015, she was named a fellow of the West Texas Historical Association. She became invested in the Great Western Trail project through her involvement in the Rotary Club of Vernon. She now lives in Fort Worth.

[ view entry ] ( 3213 views ) | permalink |

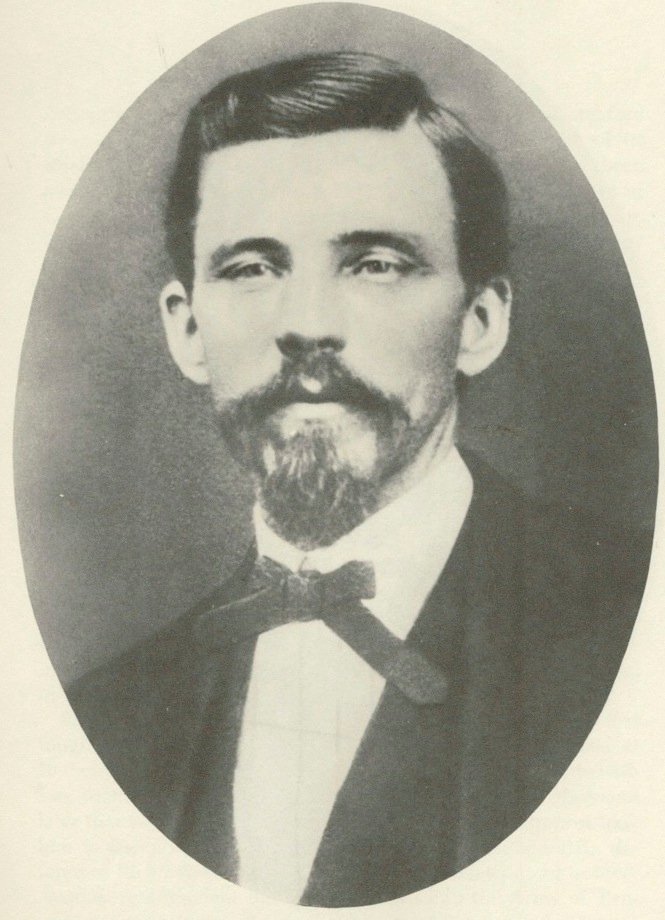

ABOVE IS A PHOTO OF JAMES WYLIE RATCHFORD

“Boys, I have done the best I could for you. Go home now. And if you make as good citizens as you have soldiers, you will do well. I shall always be proud of you. Goodbye. And God bless you all."

Robert E. Lee

April 1865

Faded and weather-beaten by more than a century of harsh sun, wind and rain, an ornately carved gravestone in the Paint Rock cemetery marks the final resting place of James Wylie Ratchford. This prominent Concho County pioneer lived an extraordinary life of seventy years, nine months and nine days leaving this world on December 3, 1910. Ratchford miraculously survived twenty-three major Civil War battles during which thousands of soldiers clad in both blue and gray gave their lives fighting for a cause they considered worthwhile. James fought in the first land battle of the war in 1861 at Big Bethel, Virginia as well as one of the last at Bentonville, North Carolina in 1865. It should also be said that seventeen other Confederate veterans rest in the Paint Rock grave yard.

James Ratchford served the Confederate States of America advancing from the rank of lieutenant to major and adjutant during his military career. Ratchford carried out duties as staff officer for three very prominent Confederate generals; Daniel Harvey Hill, John Bell Hood and Stephen D. Lee. As a staff officer for these famous Confederates, Ratchford personally delivered countless urgent dispatches and reports to Generals Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Joseph E. Johnston, and James Longstreet as well as Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Major Ratchford knew Robert E. Lee well delivering dispatches and attending meetings with the Confederate leader. Sometimes General Lee asked the young officer for his opinion in military matters. As John Bell Hood’s adjutant Major Ratchford shared the cramped quarters of a field tent and took meals with the gallant but crippled general. Hood had lost his left arm and right leg in combat but recovered remarkably and returned to the war within months. Although Hood’s aids had to help the determined warrior into the saddle he fought on to the end of the war in spite of his terrible injuries.

After the war, James Ratchford married, started a family and moved in 1879 to west central Texas to begin a new life. In 1880, Ratchford, his wife and family arrived at Paint Rock where he took a leading role in the affairs of the newly formed Concho County. Ratchford was one of the founders of the Presbyterian Church as well as the Masonic lodge. Before the establishment of a school system in the Concho County seat, the major taught twelve students in a hastily formed private school. He received a dollar per student per month for his efforts. He served as the first Concho County clerk until 1882. Ratchford took part in surveying the boundaries of the new county. As a proud Confederate veteran Ratchford and Henry Davis Pearce founded the Concho-Colorado Confederate Veteran’s Association serving as president until his death in 1910. Henry Davis Pearce served for many years as the secretary and treasurer of the association and went on to be the first postmaster and Justice of the Peace in nearby Runnels County.

I am presently working on a manuscript titled “Where Two Rivers Meet: Little Known History of Concho, Coleman and Runnels Counties, Texas”. My research has unearthed some quite remarkable stories about this part of west central Texas. Among them are the numbers of Confederate veterans who came here after the war to begin a new life. I think these are most important accounts that very much deserve not to be brushed aside or forgotten. So much of today’s politically motivated history attempts to demonize those who fought for the cause of defending their home states and establishing a new southern nation. It is an undeniable fact that the Civil War was not fought to free the slaves and started with the election of Abraham Lincoln. These Confederate veterans, particularly those from Texas, did not go to war to preserve slavery. Most never owned slaves. They fought to defend their states, homes, values and families from a punitive federal invading army. I suggest anyone wishing to dispute this point first read Charles David Grear’s excellent book “Why Texans Fought In the Civil War”. It is published by Texas A&M University. It is well researched and documented and not driven by some modern day political agenda.

After the war, great numbers of Confederate veterans came to central and west Texas needing to start over. Many had lost everything they owned in the other southern states. Of course the Texas frontier the came to was hardly much safer that the war torn southern states. These veterans came for opportunity and cheap land. My research has shown that a great many of the first pioneering settlers of Concho, Runnels and Coleman counties had some relationship or were a family member of a Confederate veteran. Their numbers are difficult to accurately state although I think it fair to say there were probably more than 1,000 Confederate veterans associated in one way or the other in these three counties. Many of these veterans became leaders in these counties in county government, church and business. They did exactly what Robert E. Lee had hoped they would do by becoming the good citizens they proved to be.

Glenn Justice

Copyright 2015

[ view entry ] ( 3625 views ) | permalink |

I have lived along the west Texas Rio Grande border on and off for many years. During this time I did a fair amount of research and writing about Big Bend border history and as a historian I cannot ignore the lessons of the past. Today Mexico is at war with itself. A massive tide of refugees is reportedly crossing our southern border. The U. S. Border Patrol is overwhelmed. The issue has become quite politicized as tempers flair with vehement demands to militarize our Rio Grande boundary. Shadowy militia groups with their own agendas have also entered the picture.

Few seem to realize that none of this is particularly new. Striking similarities exist between this present day crisis and what took place on the border a century ago. In mid-1916 President Woodrow Wilson ordered the National Guards of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, consisting of some 110,000 officers and men, to the southern border to prevent ongoing bandit raids and violence originating in Mexico. In the upper Big Bend of Texas a number of new cavalry outposts came into existence within a matter of months. For the next three years the U. S. Army, including members of the National Guard, the Texas Rangers as well as armed vigilantes took part in numerous deplorable punitive actions that destroyed the lives of hundreds of Mexicans living on both sides of the Rio Grande. Today it would be called collateral damage but that does not mitigate the inhumanity that resulted. The similarities between those times and today are striking.

Perhaps the most serious of these reprisals took place just after midnight on January 27, 1918 when Troop G of the Eighth U.S. Cavalry, Texas Rangers of Company B from Marfa, Texas and a group of vigilantes surrounded the tiny Presidio County village of Porvenir. A little more than a month previous a group of Mexican raiders had attacked the west Presidio County Brite Ranch robbing a store and stealing a herd of cattle and horses as well as shooting up the place. The raid made national newspaper headlines and initiated calls to teach border Mexicans a lesson. The some 140 residents of Porvenir were dragged from their homes into the freezing night. A search of the village turned up little; no stolen goods, only one old gun with no cartridges and a few knives. The Rangers selected fifteen Porvenir men between the ages of 16 and 72 years and marched their prisoners off into the darkness. Some distance away, the fifteen were unceremoniously shot to death. A few days after the massacre, Troop G returned to Porvenir and destroyed the village. The U.S. Army successfully covered up its role in the killings. Five Texas Rangers were fired from their jobs but never faced prosecution. The actions of the U.S. Army, the Texas Rangers and vigilantes at Porvenir went well beyond the murders of fifteen poor tenant farmers. Forty-two children lost their fathers and their homes as a result of the atrocity. The tension and border raids did not end at Porvenir however. The border raids and brutal retaliations continued on for another year and a half only ending when the U. S. Army left the border entirely in the fall of 1919.

More recently in May 1997, a member of U.S. Marine Joint Task Force 6 drug interdiction patrol shot and killed eighteen-year-old Esequiel Hernandez near the Rio Grande border as he herded goats near his family home outside Redford, Texas. Young Hernandez carried an antique single shot .22 rifle that day to fend off predators. According to the Marines, Esequiel fired a shot in their direction. He probably did not realize the Marines were nearby since they wore camouflaged “ghillie” suits. Acting on orders to return fire, Corporal Clemente Banuelos opened up killing the innocent goat herder. The Hernandez killing became a symbol of the failure of U.S. Drug policy. About that same time upriver from Redford, the Marines established a training outpost at Candelaria, Texas that operated for several summers. A U.S. Army camp about 30 miles upstream from Candelaria also went into operation. The build up of U.S. military prompted the Mexican government to move a contingent of several thousand troops from Chiapas to the border to counter the U.S. troops just across the river. For more than a year the Texas upper Big Bend once had again became an armed camp with soldiers from two nations separated only by a small stream of water known as the Rio Grande River. Citizens on both sides of the border were alarmed and things only quieted down when both the U.S. and Mexican forces left the area much to the relief of border residents.

Texas Governor Rick Perry’s recent decision to order 1,000 national guardsmen to the Mexican border is an ill advised political move. At a cost of about $12 million dollars a month, the militarization will only increase border tensions as it always has in the past. These guardsmen have highly questionable arrest powers and lack training in law enforcement. Many of them cannot speak Spanish only adding to the difficulty. Let the Border Patrol and local law enforcement carry out their job, a job they are trained to do and give them the necessary support and funding needed. As Winston Churchill put it, “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”.

Glenn Justice

[ view entry ] ( 3621 views ) | permalink |

Bob Alexander’s "Riding Lucifer’s Line" is a well researched collection of twenty-five sketches about Texas Rangers who died by gunshot in the performance of their duties along the Texas-Mexican border between the years 1875-1921. Writing from the knowledgeable perspective of a retired U.S. Government Treasury officer, Alexander undertook a formidable task piecing together the often-obscure and many times incomplete life stories of these selected lawmen. This is not an easy task. Historical records relating to Texas Rangers are frequently spotty and incomplete for a variety of reasons. Some were lost to fire or other calamity while others curiously somehow vanished from state archives, county courthouses and other repositories. These Rangers commonly moved from job to job inside and outside law enforcement seldom staying in one location or position for long periods. Pay was low, hardship plentiful and life threatening danger a constant factor.

Alexander’s Rangers met death in a variety of ways ranging from accident to ambush with a surprising number being the result of inexperience and the absence of modern tactical training. Early day Rangers had to learn law enforcement mostly by performing the job and sometimes this in itself proved deadly particularly on the Texas-Mexican border. An example of this was the 1890 death of Texas Ranger Private John H. Gravis in Presidio County. Gravis had been a Ranger for about five months when he and a deputy sheriff got into a gunfight in the rowdy silver mining town of Shafter. The young Ranger lost his life after being shot in the head. While conflicting accounts cloud the details Alexander pointedly summed up the tragedy by writing “On the Texas/Mexican border rookies were but the raw meat of the devil”. Another example emerged with the death of Ranger Robert E. Doaty some two years later. Doaty had been a Ranger for only twenty-two days when he met death in another border shoot out. The same is true for Eugene B. Hulen killed in Presidio County in 1915 after being a Ranger forfifty-seven days.

Although the author’s wordy writing style might burden some, Alexander does offer the dedicated reader an insight infrequently found in the innumerable volumes of Texas Ranger history. The author avoids the Texas Ranger mythology pitfalls of Walter Prescott Webb and others painting a realistic and sometimes gritty picture of these lawmen as they met their end. There are no stereotypes present in these stories. In a lengthy two-part introduction Alexander lays out his premise in which he acknowledges the wrongs and abuses of some pre-modern era Rangers. He traces the evolution of the Texas Rangers from their early days as Indian and bandit fighters and gunmen to today’s lawmen through advancements in transportation, tactics and technology. While Alexander promises, “no white washing” in his effort he does somewhat subjectively present the lawman’s point of view relegating divergent analysis to being somehow less than creditable. While Alexander seems to disdain the work of agenda driven scholars and those he considers to be “armchair historians”, he does not hesitate to make use of such research.

No one doubts that law enforcement on the Texas-Mexican border is and always has been a very risky but necessary profession. It is also controversial mostly during the bloody years of the Mexican Revolution. This book will probably appeal more to Texas Ranger enthusiasts and less to those persuaded by revisionist views. However, it is an insightful work deserving consideration by all. These Rangers who gave their lives certainly merit inclusion in the pages of history. How and why they died is a worthy topic for reflection. Alexander’s effort is to be commended. As Louis R. Sadler put it “This is Bob’s best book to date” and it is.

"Riding Lucifer’s Line: Ranger Deaths Along the Texas-Mexican Border". By Bob Alexander. Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2013. Pp. xxvi, 404. Photographs. Notes. Bibliography. Index. $29.95 cloth.

Glenn Justice

Used with contractual permission of

"The Americas: A Quarterly Review of Inter-American Cultural History"

Copyright 2014

[ view entry ] ( 3854 views ) | permalink |

<<First <Back | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Next> Last>>